by Ludovica Sebregondi

Palazzo Strozzi, a milestone in the development of Italian Renaissance architecture, is one of the most elegant and best-known examples of these prestigious buildings that began to be erected in the 15th century with their large courtyards surrounded by columns acting as the focal point around which the entrances and staircases converged. The courtyard was unquestionably a showpiece, but it also made life in the palazzo far more pleasant thanks to the cool shade offered by the portico on the ground floor, the two airy loggias on the first floor and the loggia on the attic floor, which was a veritable suntrap in winter.

Romanian Academy Library, Bucharest.

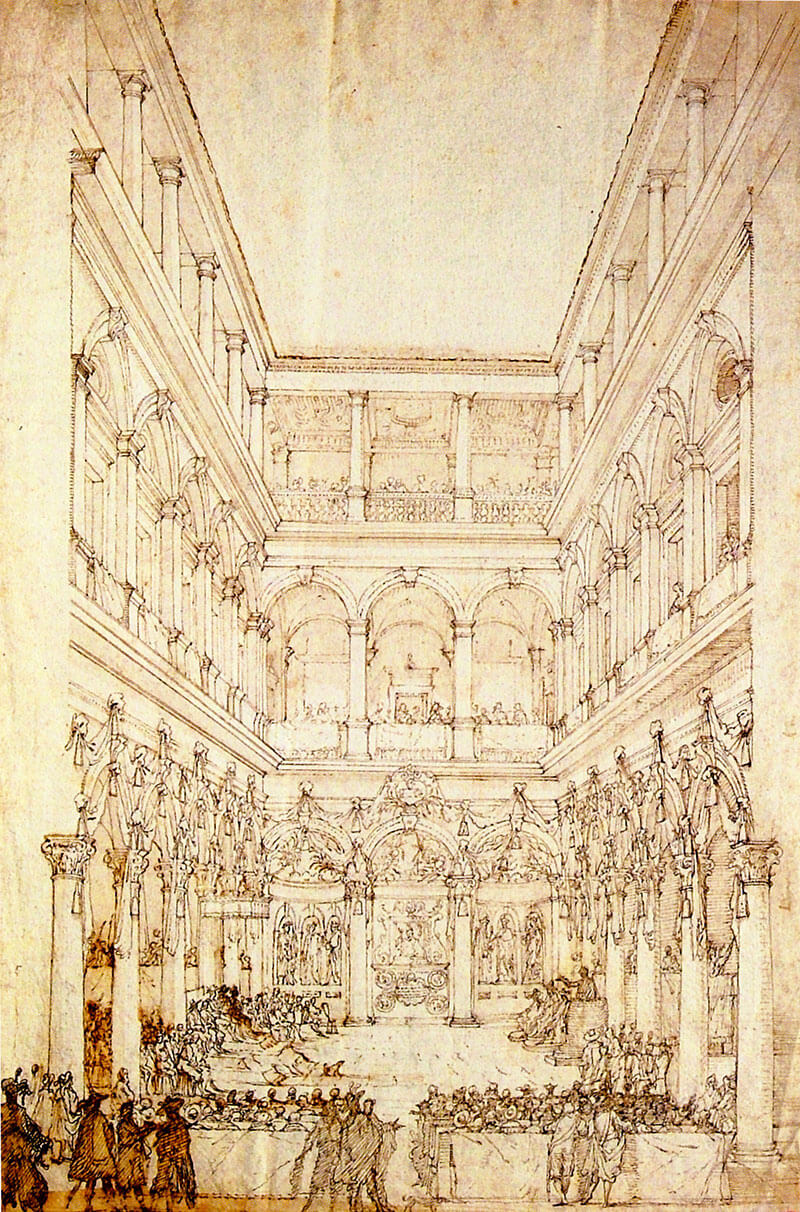

We owe the courtyard of Palazzo Strozzi to Simone del Pollaiolo, known as Il Cronaca, who was the palazzo’s supervisor and executive architect from 1490, shortly after construction began, until 1504. A perfect setting, it has also been used as a theatre and auditorium, for instance for assemblies held by the Accademia della Crusca in the 17th century such as the assembly held in the presence of Grand Duke Ferdinando II de’ Medici, illustrated in a pen drawing by Alfonso Parigi and described by Francesco Settimanni in his Diario:

On June 10th 1651. The Accademia della Crusca of Florence gathered in the Courtyard of Messrs. Strozzi’s Palazzo by the Canto a’ Tornaquinci, where the Signor Cavaliere Rucellai delivered a very fine Oration in praise of St. Zenobius, Bishop of Florence, who was chosen as the Patron of said Accademia; and many splendid Compositions were recited, and all the Most Serene Princes were in attendance with much of the nobility.

Photograph from the panels in the Museino di Palazzo Strozzi.

But the centuries went by, ushering in the modern age, and by the early 20th century the courtyard was being used as a “carport” for Piero Strozzi’s motor car, the first ever seen in Florence: a 6HP Panhard-Levassor, which was the model that won the 1897 Paris-Dieppe race. The palazzo remained in the family until 1937, when it was sold to the Istituto Nazionale delle Assicurazioni which made it over to municipality. Restoration work began in that same year and was completed by 1940, when the building’s new role was inaugurated in the presence of King Victor Emmanuel III with a major Exhibition of the Tuscan Cinquecento in Palazzo Strozzi. The Palestrina Pietà, thought at the time to be by Michelangelo and recently acquired by the Galleria dell’Accademia, was placed in the courtyard and chosen as the logo for the event.

Photo Martino Margheri

The same viewpoint that we see in the 17th century drawing was revived in Paola Pivi’s monumental Untitled Project installation in 2015, comprising a colourful inflatable ladder over 20 metres tall that took the contrast between classic and contemporary to new heights. The ladder was an object emptied of all practical use, oversized, unstable and temporary: an evocative kaleidoscope marking a break with tradition in total contrast with the controlled and symmetrical perspective of its Renaissance architectural setting and with the measured hues of the courtyard’s grey pietra serena and white plaster colour scheme. The artist’s aim with this surreal graft was to trigger an emotional shock, smashing the accepted conventions of space to create a new and unexpected meaning.

In some ways it felt as though she was trying to evoke what had been known as “the monstrosity”: “a two-ramp staircase rising from the heart of the Renaissance courtyard right up to the loggia on the third floor,” “brutally” cutting it in two and making it impossible to perceive in its entirety. The “monstrosity” was erected in the summer of 1983 ahead of the 13th Antiques Biennale (17 September–9 October), when it was described in the catalogue as “a huge surprise as well as a novelty.” The massive public outcry against the invasive structure was taken up by figures from the world of culture such as Eugenio Garin and by glossy magazines such as “Casa Vogue.” The fire escape was subsequently dismantled, but for years it was an eyesore defacing a perfect space and Paola Pivi’s work may well have been an allusion to the countless structures that have marked and blighted the silhouette of so many monumental buildings.

In 2018 Carsten Höller used another modern material in his Florence Experiment Slides installation to build two monumental helical slides allowing visitors to slide down the 20 metres separating the second-floor loggia from the courtyard in a matter of seconds. The work emphasised the architectural space, accentuating its upward thrust and pursuing the dialogue between old and new with the use of steel and polycarbonate to create a structure with a gradient of 28°. Each slide was approximately 50 metres long, weighed roughly 3,600 kilos, making an overall weight of over 12 tonnes, and was held together by 265 bolts, as many nuts and 522 washers. These cold figures offer a technical description of the structure, yet quite apart from the innovative scientific experiment associated with it (devised in conjunction with plant neurobiologist Stefano Mancuso), the impressive thing about it was the tangle of arms reminiscent of the Laocoön, but that also reminded us of the ongoing practice of causing façades and courtyard to interact with temporary and contemporary structures.

Cover: Carsten Höller, The Florence Experiment Slides, 2018, Photo Attilio Maranzano