Every week the Palazzo Strozzi newsletter reveals a word or term linked to the artists and works on display in the American Art 1961-2001 exhibition, creating an original glossary to explore themes and connections.

To tie in with the American Art 1961-2001 exhibition, the Fondazione Palazzo Strozzi, in conjunction with Florence University’s SAGAS (History, Archaeology, Geography, Art, Performance Arts) Department, has developed a project entitled One word a Week, a formative experience for 14 girl students taking the master’s degree course in art history designed to create an on-line glossary enabling all of Palazzo Strozzi’s visitors to explore the exhibition in greater depth.

In the course of a series of remote encounters (October 2020–February 2021) the students explored the works, artists and themes of the American Art 1961-2001 exhibition, analysed the communication materials used by Palazzo Strozzi (explanatory panels, captions, timelines, family texts) and selected 14 key words for exploring the show in greater depth with the intention of making a number of concepts that recur in 20th century art accessible to all. In drafting the glossary, they alternated independent writing sessions and moments of collective revision, with the aim of clearly illustrating the various phases that lead to the drafting of a text.

Each entry in the glossary corresponds to a room in the exhibition, explains a term and sets it in context in relation to the work of the artists on display in the exhibition. Students involved in the project: Lida Artusio, Veronica Betti, Chiara Ciagli, Irene D’amato, Alessia D’Annunzio, Gioia Dipaola, Evelyn Monia Ferro, Francesca La Rocca, Sonia Luppi, Cristina Marcelli, Camilla Marruganti, Francesca Pinna, Caterina Vagniluca and Federica Valleise.

Photos: American Art 1961-2001, exhibition view, Palazzo Strozzi, Firenze, 2021. © photo Ela Bialkowska, OKNOstudio

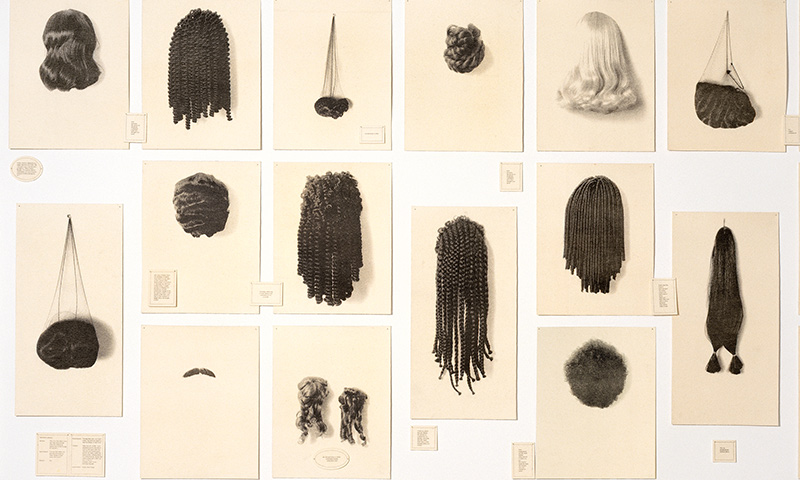

Cover: Lorna Simpson, Wigs (portfolio) (det.), 1994, Minneapolis, Walker Art Center. © Lorna Simpson. Courtesy the artist and the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis

In industrial production the term assemblage stands for a series of operations required to put together the parts of a device or item, while in art the concept of assemblage refers to the creation of a work of art by juxtaposing materials of different origin.

The Futurists and the Cubists were the first to resort to this kind of approach by taking objects, either whole or in pieces, new or with a previous life, and building them into their creations. Items removed from their original context and assembled together enter the art world in the guize of new materials for artists to create with. The technique known as assemblage extends the practice of collage into a spatial dimension and allows the artist to transform a neutral object without any obvious aesthetic merit into a new artistic creation.

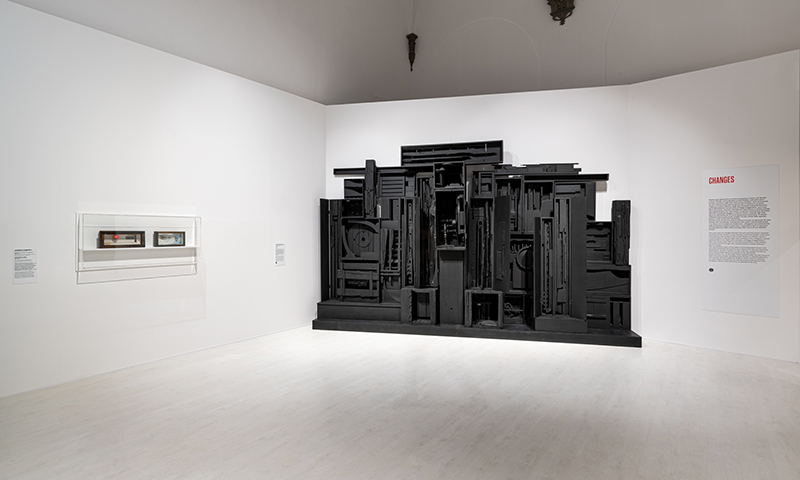

Artists such as Louise Nevelson (1899–1988) and Joseph Cornell (1903–1972) resorted to the practice of assemblage seeking inspiration in everyday objects, collecting fragments and remnants of daily life and building them into their work.

Nevelson was inspired by forms and surfaces weathered by time, by what she called “the crap I see out my window”, and for her creation was a search for order, for “a great symphony where there was nothing left out.” Nevelson sometimes painted the assemblages she made with fragments of wood black, harmonizing the various parts into a whole on which the color conferred a mystical, magical aura.

Cornell explored New York, wandering around antique shops, knicknack stores and second-hand bookstores. He loved the sensation of pleasant surprize he felt when he found something that fascinated him and he treasured these objects, assembling them in reliquary boxes in which he created a dimension suspended in time and space.

Irene D’Amato

The term seriality indicates things arranged in a specific order or repeated in sequence to form a series. The work of artists such as Andy Warhol (1928–1987) and Roy Lichtenstein (1923–1997), both associated with Pop Art, addressed the image of the consumer society that developed in America in the aftermath of World War II. Their art embraced subjects of popular culture and resorted to techniques involving the serial production of images, an approach that had more to do with the worlds of advertising and industry than it did with the world of art.

Andy Warhol, who was inspired by the language of advertising, developed an impersonal style in which he quashed his own subjective input to interpret the aspirations of others: “if you can’t beat the consumer society, then you’re better off joining it, or even exposing it.”

Using the technique of silk-screen on canvas, Warhol simplified the images disseminated by the press and by advertising, making them repetitive and seemingly superficial through serial reproduction. He applied this approach both to Campbell Soup, reproducing the various flavors, and other items of everyday use that became icons of a lifestyle, and to celebrities such as Marilyn Monroe and Jackie Kennedy, or to images of disturbing events such as car accidents or the electric chair.

Roy Lichtenstein also gave his work a serial character. At a time when cartoon strips were growing in popularity, the artist took illustrations, enlarged them and removed them from their original context. Copying the way the typographic screen produces hatching in the shape of small dots, Lichtenstein imitated the serial and mechanical printing process in an artisan manner.

Evelyn Monia Ferro

Intermediality refers to artistic creations in which different media coexist in a single context. The term was coined by Dick Higgins (1938–98) in his essay Intermedia (1966) to identify an artwork characterized by “music which is not Music, poems that are not Poetry, paintings that are not Painting, but music that may fit poetry, poetry that may fit paintings.” Intermedial work is thus a product of dialogue and collaboration between artists in different disciplines, and the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis has an important collection of works of this kind because since 2011 the museum has housed the archive of choreographer Merce Cunningham (1919–2009), an interdisciplinary artist open to collaborations, whose approach to art is held up as a model of intermediality.

Cunningham’s method is based on the concept of chance: a necessary tool to create “unpredictable” choreographies, in other words exhibitions that are always open to unexpected moments of amazement. In his important collaboration with composer John Cage (1912–2002) Cunningham prepared his choreographies without music, in total silence, while Cage composed his music without regard for the choreography. As the composer put it: “Whether it’s an amusing piece or a serious piece, we simply work separately and put things together in the theater.” Similarly, Cunningham describes his collaboration with Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008) for the choreography entitled Minutiae (1954–76) as an “a collaboration at once exciting and ‘excruciating,’ in which neither one knew what the other was doing until the last moment,” thus revolutionizing the traditional relationship between dance and music.

Chiara Ciagli

Hard-Edge Painting is a definition coined by Californian art critic Jules Langsner in 1959 to describe painting with sharp contrasts and broad monochromatic fields of color popular in the United States in the 1960s. Simplicity of form and stringency of color, together with recourse to abstraction, are typical features of Hard-Edge Painting that have a precedent in the work of Piet Mondrian and Joseph Albers, two early 20th century artists that laid the groundwork for abstract geometric painting with basic color choices. Artists generically termed Hard-Edge artists share an interest in painting reduced to a minimum dominated by the chilly nature of its compositional choices and by emotional detachment. These works are objective in nature and are in sharp contrast with the emotional and personal involvement of the Abstract Expressionists, the generation of American artists that dominated the scene in the 1940s and 1950s with their large abstract canvases imbued with biographical experience and existential anguish.

Ellsworth Kelly (1923–2015) was one of the most celebrated exponents of Hard-Edge Painting. His painting is characterized by elementary geometric forms with sharp outlines: compositions of primary shapes often inspired by his observation of the shapes of everyday items that he enlarges until they become unrecognizable. Kelly said: “I like to work from things that I see, whether they’re man-made or natural or a combination of the two.” In his work we consistently find monochromatic fields of bright color, the nuance of chiaroscuro is totally missing, shape and color coincide. The profile of the geometric figures depicted occasionally impacts the shape of the picture which thus loses its traditional rectangular form to become a uniquely-shaped object hanging on the wall.

Federica Valleise

The expression Minimalism, used to describe a tendency to reduce things to their bare bones, is applied in numerous different fields including architecture, art and design, and it can even be used to describe a particular approach to life.

“Less is more”, the phrase coined by the architect Mies van der Rohe (1886–1969) to open his manifesto, sums up the essence of Minimalism in three words. In art history, Minimalism is a movement that developed in the United States in the 1960s as a reaction to Abstract Expressionism and to Pop Art. Minimalist artists’ work tends to be characterized by a search for purity of form reduced to elementary geometric structures devoid of any symbolic or emotional referent. This chilly aspect is also reflected in their use of new, industrially manufactured materials such as steel, concrete, neon tubes and plexiglass.

Artists who drew close to Minimalism, albeit while rejecting the label as such, include Frank Stella (1936), Dan Flavin (1933–1996), Carl Andre (1935), Richard Serra (1939), Anne Truitt (1921–2004) and Donald Judd (1928–1994), the group’s thinker and theoretician.

In 1965 Judd shared his ideas in an essay entitled Specific Objects, where he uses that definition to define works of art that cannot be classified either as sculpture or as painting. The artist applied this concept to his own work, creating modular sequences of repeated elements whose shape remains the same while their colors, quantities and proportions change.

Dan Flavin’s work, made of fluorescent tubes, opened up a new relationship with space which he occupies with neon lights reconfigured in geometric forms and invades with the dazzling light that they emit. As the artist put it, a Minimalist work of art: “…is what it is and it ain’t nothing else. Everything is clearly, openly, plainly delivered. There is no overwhelming spirituality you are supposed to come into contact with”.

Camilla Marruganti

The term performance art indicates an artistic genre in which the artist’s body is their chief tool for expression, and it is differentiated by its ephemeral and immaterial nature. In 1970 artist, curator and published Willoughby Sharp (1936–2008) wrote: “Young artists have turned to their most directly usable resource, themselves as material for sculpture, with almost unlimited potential.”

Performance art satisfies the need for a break with the traditional disciplines and economic rationales typical of the art market, which is interested in the production of items that are easy to sell. The works covered by this definition include a multiplicity of experiences very different the one from the other: there are meticulously planned performances, others left entirely to the creative possibilities of chance, actions in which the relationship between the artist and the audience, which plays an active role, is of the very essence, or others that are performed in perfect solitude to be recorded through photographs or on video, as for example the work of Bruce Nauman (1941). Nauman moves about between various different expressive forms, mixing sculpture, performances, interactive installations and videos, pointing to his recurrent interest in the depiction of the body and the use of language. In his studio performances, Nauman replaces an audience with a cine camera recording simple actions, often repeated obsessively: walking, pinching himself, playing an instrument or meticulously painting his own body in a sequence of four colours as in his piece entitled Art Make-Up performed in 1967–8. Nauman stated drastically that: “If I’m an artist and I’m in a studio, that means that whatever I do in this studio is art”.

Cristina Marcelli

The term Conceptual Art, which was first coined in America in the early 1960s, describes an approach to artistic production in which ideas and concepts form the basic elements of the artwork to the point where they acquire far greater importance than the work’s physical production or aesthetic value. While Pop Art emphasizes the objects and symbols of the consumer society, Conceptual Art moves away from that visual panorama and from the emotional aspects of images. Artists close to this trend identified the essential nature of art as lying in the expression of ideas, thus they avail themselves indifferently of such different media of communication as sculpture, painting, photography, video, publications, industrial materials and even their own bodies.

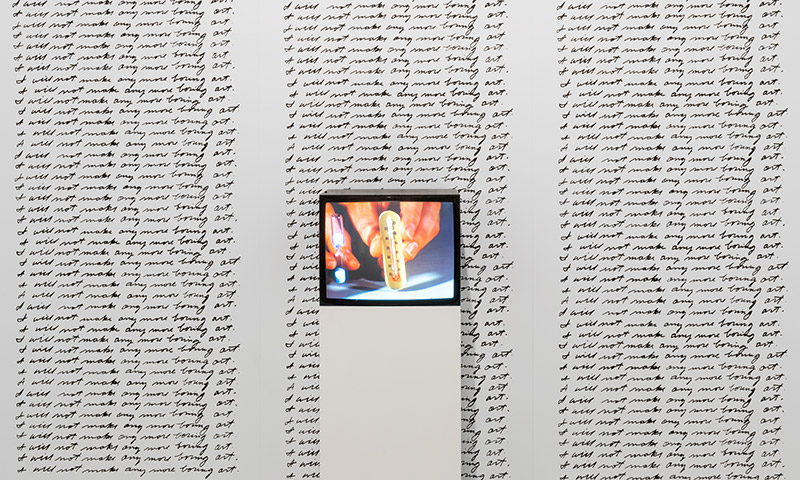

John Baldessari (1931–2020), one of Conceptual Art’s pioneers, adopted several artistic languages in his work. His artistic practice was based on the combination of texts and on the appropriation of images taken from magazines or movie stills, offering an ironic, humoristic and often irreverent vision in opposition to the stringency that characterized much of the movement’s work. Typical of his approach is the video in which the artist’s hand is filmed as it writes the sentence I will not make any more boring art, from which the work gets its title. Baldessari carries on writing without a break for thirty minutes as though it were a punishment, pointing up the inconsistency between the (boring) gesture and what the sentence actually says, thus creating a game within a game in which the subject of the work and its realisation coincide.

Alessia D’Annunzio

The word AIDS (Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome) entered people’s daily vocabulary in the early 1980s. The acronym refers to a disease of the immune system caused by the HIV virus that has killed millions. Until the mid-’90s the conservative politics of US President Ronald Reagan, British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and German Chancellor Helmut Kohl showed a deep lack of sensitivity toward the AIDS epidemic. These governments evinced a lack of interest in the spread of the virus, homosexuals were sidelined and homophobia was a very common attitude. In response to the institutions’ indifference, 1987 saw the birth in the United States of ACT-UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) whose aim was to “engage in direct action to put an end to the AIDS crisis” and many artists signed up. The organization’s symbol is a pink triangle on a black ground with the motto “Silence-Death.” That same year American art historian Douglas Crimp, an LGBTIQ+ rights activist, wrote in his essay AIDS Cultural Analysis/Cultural Activism: “We don’t need a cultural renaissance; we need cultural practices actively participating in the struggle against AIDS. We don’t need to transcend the epidemic; we need to end it,” calling on the institutions to intervene against the AIDS Community’s marginalization. In a society in which the word homosexuality is banned, art and activism become the only tools for denunciation, as we can see from the work of Robert Gober (1954), an openly gay artist who sees himself as a survivor. Felix Gonzalez-Torres (1957–1996) on the other hand, who died of AIDS, addresses the theme from a more intimate and personal viewpoint, linking it to his own personal experience: in “Untitled” (Last Light) he symbolically uses light bulbs to depict the fleeting nature of life and to immortalize his partner Ross who died of the disease in 1991.

Veronica Betti

The term Appropriationism is associated with the concept of appropriation, in other words taking possession of something that belongs to others with the intention of making it your own. In artistic terms the practice consists of reusing images, pre-existing artworks and objects, and either modifying them or not. Appropriation as a creative approach dates back to the early 1900s and its leading exponent was unquestionably Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968). The inclination to “steal objects and images” came to the fore also in Pop Art, peaking out in the ’70s with a new generation of artists that further radicalized the concept. In 1977 critic and curator Douglas Crimp organized an exhibition at the Artists Space Gallery in New York entitled Pictures in which he brought together artists whose work involved the appropriation of others’ images and in a critique of originality, a crucial element. The exhibition laid the groundwork for a debate that was picked up by such artists as Barbara Kruger (1945), Sherrie Levine (1947), Robert Longo (1953) and Richard Prince (1949), who imparted a new meaning to images, subverting the value of authenticity and authorship. Many resorted to photography on the grounds that it was the language best suited to exploring the shaky boundaries between originality and reproduction, in addition to being the very language that advertising and the mass media use to convey specific social constructions. With his series entitled Cowboy Richard Prince rephotographed Marlboro cigarette ads before enlarging them and getting rid of the writing, thus generating a further level of ambiguity: “Even if I’m aware of the classic nature of these images, I find myself chasing after images that don’t seem totally believable to me. And I seek to re-present them in an even less believable way.”

Francesca Pinna

By under-represented communities we mean those groups of people who represent a minority part of the community to which they belong and who are distinguished from the majority of the population by their ethnicity, their religion or their language. Under-represented communities, precisely on account of their diversity, should be seen as a source of cultural enrichment for society, but they have been the target of discrimination since time immemorial. The injustices perpetrated to the detriment of under-represented communities triggered demands and struggles that made a deep mark on the history of the United States: this tension led to the birth of movements for the abolition of slavery in the 19th century, for civil rights in the 1950s and ’60s, for women’s liberation and emancipation and for the recognition of ethnic minority communities’ and gay communities’ rights in the ’70s.

Hock E. Ave/Edgar Heap of Birds (1954), a member of Cheyenne and Harrapao tribes, commemorates with his art those who have fought identity-related battles, which they have often lost but which have served to trigger cultural change. The artist creates works that address stories of repression and violence on the part of the state and of settlers against native communities in the United States, drawing parallels between historical violence and the injustices of today.

Membership of an under-represented community also comes to the fore in the work of Lorna Simpson (1960), an artist of African descent who underscores the weight of discrimination against the Black community. Her work Wigs (porfolio) explores the history of African American hairstyles and the conventions surrounding beauty. Natural hairstyles are a symbol of identity-related demands and emancipation pitted against dominant aesthetic standards, thus hair acquires social and political implications.

Gioia Dipaola

The German word Gesamtkunstwerk (i.e. “total work of art”) refers to a fusion of artistic languages that mutually complete each other to form a perfect synthesis. This approach, theorized by Richard Wagner in 1827, continues to exist even today in many works of art, and Matthew Barney’s The Cremaster Cycle is a perfect example of it.

The work is divided into five feature films produced between 1994 and 2002, in which the artist cause the study of religions, mythology and the human urges at the origin of life to converge. In exhibits the video work is often accompanied by photographs, drawings, sculptures and objects used in the films, causing the work to take on a scenographic dimension.

Cremaster 2 (1999) is the second narrative episode in the cycle written and played by Matthew Barney. The feature film takes its cue from the 1977 case of Gary Gilmore, a Mormon who, after confessing to two murders, requested execution by firing squad in order to follow the precepts of his faith which calls for the shedding of one’s own blood in expiation of his sins. The film also contains references to Gilmore’s relatives: his sensitive grandmother, his parents involved in a mystic vision associated with bees that led to Gary’s conception, and an echo of his alleged descent from the escape artist Harry Houdini.

The Cremaster Cycle has been defined by numerous critics as the Gesamtkunstwerk of the multimedia era. The concept of total work of art in Barney is also linked to the title of the cycle, because the Cremaster – a muscle present in the testicles – is in this instance an allegory for the creation of life and its endless metamorphoses.

Sonia Luppi

California, a US federal state, was one of the economic, political and cultural driving forces behind the American dream, which consists of blind faith in the ability to improve one’s quality of life through personal commitment. The crumbling of that hope in the 1960s sparked a deep crisis and led to the birth of a youth counterculture known as the Beat Generation and the Hippy movement whose epicenter was precisely in this state. California in the ’90s was known for surfing, for the movie industry, for the porn industry and for hip-hop; then it became the most densely populated state in the Union and its inhabitants rank among the most ethnically varied anywhere in the world. Yet events such as the Los Angeles uprisings of 1992 highlighted the state’s deep underlying social tension, prompting artists to focus on such issues as under-represented communities and LGBTQ+ rights. California today is a leader in global development and is home to some of the world’s leading hi-tech corporations such as Youtube, Google, Apple and Facebook. New York is no longer the unquestioned capital of contemporary art. Artistic and cultural production has shifted to California in search of experimentation and of a renewed sense of community, also encountering there one of the wealthiest societies in the world that supports such cultural entities as the Institute of Contemporary Art and The Broad, a museum of contemporary art. An entire generation of artists has either trained or moved to California and cooperates with its institutions, producing works that are a lively expression of American art: the presence of Mark Bradford (1961) representing the United States at the 2017 Venice Biennale provides tangible evidence of that.

Lidia Artusio

By silhouette we mean a black image on a white background, fashionable in the second half of the 18th century, reproducing the profile of a subject by supplying only an outline whose interior is has been darkened like a shadow. This technique was especially widespread in the Victorian era as a hobby for well-to-do ladies, but Kara Walker (1969) rediscovered it and reinterpreted it, overturning its viewpoint, A new politicized art form began to emerge in the 1990s and criticism of racial conventions and of social constructions also involved recours to alternative artistic genres. The artist of African descent adopted the strategy of the “stereotypical grotesque” to showcase and thus denounce the symbols of the racist tradition. Walker explores American history in works that tell stories, from before the Civil War, of slaves and plantation owners in the South involved in scenes of sex and violence. The themes addressed and the caricatural figures are reduced to mere outlines of their true selves, human beings that are not totally complete. Casting their critical gaze on the past, Kara Walker’s works offer food for reflection on the present, on the ongoing existence of cultural models in contemporary society. The artist sees silhouettes and stereotypes as “closely linked because they both say a great deal with not much information.”

Francesca La Rocca

Video Art is an artistic language that resorts to systems for recording and reproducing images in motion and it is closely linked to technological progress and to the expressive potential of video. Video Art was born in 1965, when Sony first marketed its Portapak, the world’s first portable cine camera which paved the way for the birth of this art form. In the 1960s artists linked to the interntional movement called Fluxus contributed to disseminating the use of the language of video, but the artist who played a crucial role in getting Video Art off the ground was South Korean artist Nam June Paik (1932–2006) who used a television as artistic material for the first time in 1963. In the middle of the decade Paik produced modified televisions, connecting television sets to interactive radio controls to make sound “visible” on the screen. In 1971 he built a TV Cello, a musical instrument-cum-sculpture produced with screens capable of broadcasting television and video recording content for using during wild musical performances. Paik said that a man’s life is strongly impacted by technology and the aim of his work was precisely to “humanize technology” in order to strike a balance between the parts.

Dara Birnbaum (1946) also works with video but devotes a very different kind of attention to images in motion. The artist is known for her revolutionary video production strategies in which she even uses modified fragments of television programs. One of her most important works is Technology/Transformation: Wonder Woman in which she critiques the vision of women that society proposes and the absence of a realistic model midway between the heroine – in this instance Wonder Woman – and the secretary, thus preventing them from discovering their true identity.

Caterina Vagniluca