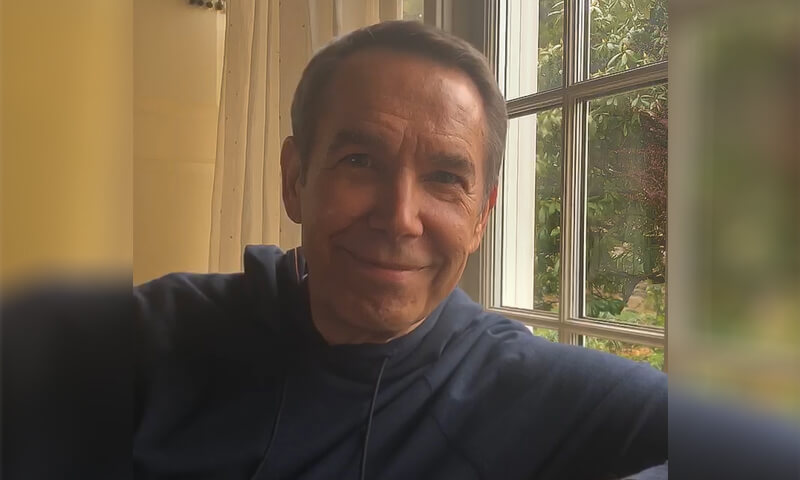

by Stefano Mancuso

The director of the Laboratorio Internazionale di Neurobiologia Vegetale (LINV) and a scientist of worldwide prestige, Stefano Mancuso makes his own personal contribution to the IN TOUCH project after cooperating with the artist Carsten Höller on The Florence Experiment project in Palazzo Strozzi in 2018. Renowned for his work on the cognitive capabilities of plant life, Mancuso turns here to discussing such concepts as the intelligence, reproduction and extinction of living beings, in a controversial debate that prompts us to ask ourselves the question: are we really sure that man is superior to other species? “An apricot tree can’t do a great deal to bring about its own extinction, nor indeed can a cow. Mankind, on the other hand, constantly generates new ways of bringing about his own extinction.”

Life is a cognitive process.

It’s impossible to imagine life without cognition. After all, how can anyone imagine a living being incapable of resolving problems, incapable of displaying “intelligence”? In order to survive, even the simplest organism needs to be able to resolve problems at every moment of its existence. Yet flying in the face of this obvious consideration, man has always thought that he was the only intelligent being, or at least one of only a handful and in any case the smartest of the bunch, with little or nothing in common with the rest of life. To corroborate this image, we’ve always imagined that our characteristics are unique too. The chief source of our supposed superiority is, of course, to be sought in our large brain and in its enormous capacity for logic which allows us to do things that other living beings are incapable of doing: we can write, we can paint, we can develop theories and we can compose symphonies. But does this skill really differentiate us from other living beings? And perhaps more importantly, does it make us superior to other living beings?

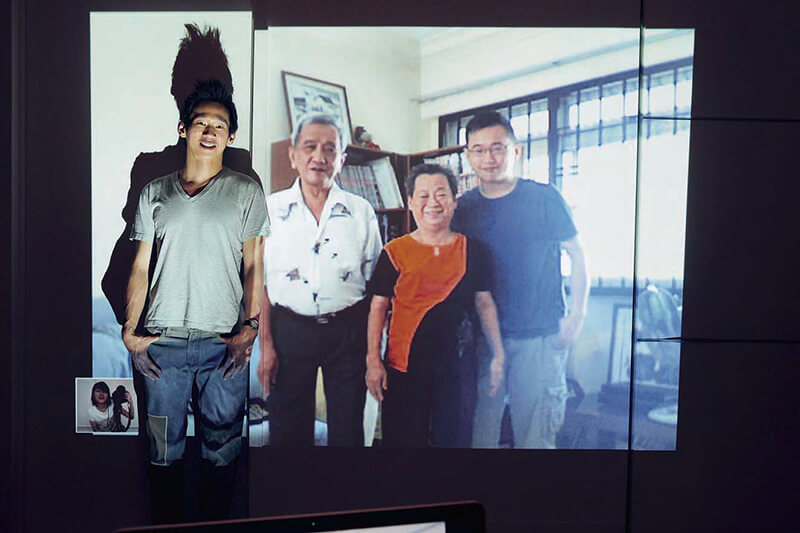

Photo Alessandro Moggi

Man has always endeavoured to define such concepts as intelligence, the mind and cognition in such a way as to restrict them to his own species. To do this, he has developed increasingly stringent notions of what intelligence and cognition are.

But he hasn’t always achieved the hoped-for results. Is intelligence the ability to use tools? If it is, then there are plenty of animals who use tools. Does intelligence concern the ability to develop abstract thought? Plenty of primates, and indeed other beings, are capable of developing abstract concepts.

Intelligence must be explored like a fully-fledged biological principle, in a very similar way to the way we consider reproduction. Every living being has the ability to reproduce. Life reproduces itself, life creates itself: reproduction is one of the fundamental principles of life. Who would ever think of arguing that only mankind reproduces? Of course, there are different and very complex ways of doing so. Mankind reproduces on the basis of a fairly complex set of rules, while plants have highly original reproductive systems and funghi, insects and bacteria reproduce in a manner so totally different that the phenomena cannot readily be likened to one another. Yet they all share the same result, which is the reproduction of life. And sure enough, the dictionary definition of reproduction is as broad as it can be: “the ability to multiply.” No mention is made of specificity. Human specificity is of little significance in respect of the way other forms of life reproduce. We should look at intelligence in the same way, considering it to be a fundamental property of life that should be defined in as broad and as inclusive a manner as possible, for example by defining it as the ability to resolve problems and thus a feature shared by all living beings.

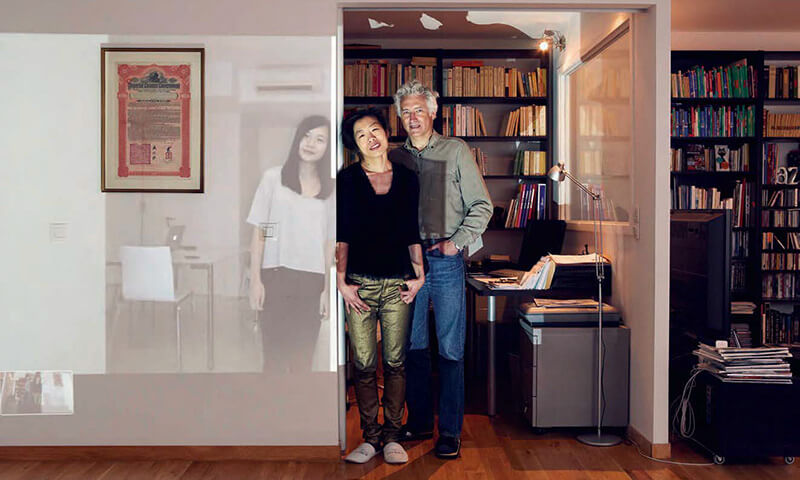

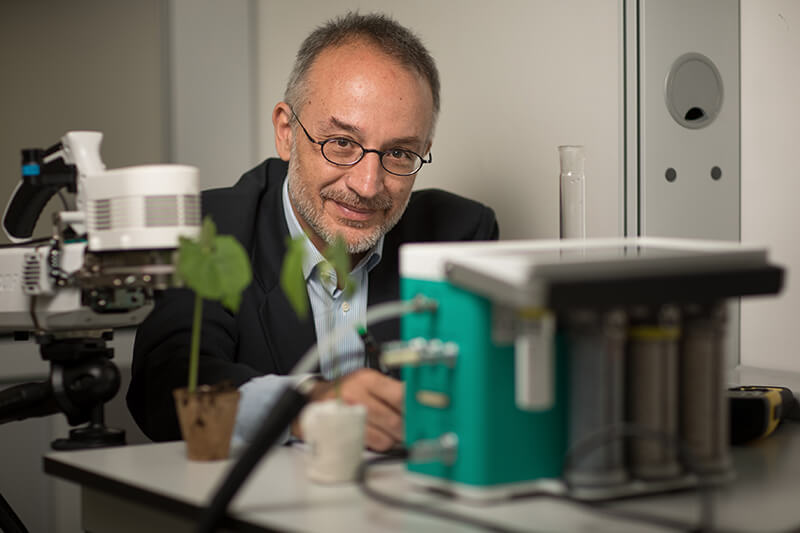

Carsten Höller and Stefano Mancuso, The Florence Experiment, 2018

Photo Alessandro Moggi

So now we need to ask ourselves where we get this notion of superiority. How come we consider ourselves to be in a different and superior category to other human beings? I’m almost certain that every one of us thinks he or she is superior to a cow, an apricot tree, a worm or a bacteria. Anyone disagreeing would be telling a lie. Darwin tells us that evolution is the survival of the fittest, a law we can’t shirk, a law as immutable as the law of universal gravitation. But why didn’t Darwin use the word “best” rather than “fittest”? Well, because in the context of life, the words “better” and “best” are a nonsense. “Better” than what? Being “better” only means something if you have a goal. For example, if the aim is to jump highest, then a person who can jump 2.10 mt is “better” than one who can only jump 2.00 mt. Yet the crucial aspect of life is that the end goal is the ability to survive and to propagate one’s own species. Now that we have a slightly clearer picture, we can ask ourselves whether man, with his special intelligence and his large brain that allows him to develop theories and to compose symphonies, sonnets and so on, is more or less “fit” to survive than other species. If we adopt this far more appropriate viewpoint, we have no choice but to change our minds with regard to the contention that we’re “better,” because it’s been estimated that the average life of a species is about 5 million years. Naturally, there are species that are much longer-lived, for instance conifers, ferns, mosses and even crocodiles: all of them, species that first put in an appearance tens of millions of years ago and that are still around. But never mind them. Let’s just consider the average life of a species, which is 5 million years. Homo sapiens first appeared about 300,000 years ago. We’d have to survive another 4,700,000 years just to hit the average mark, and we’d have to last a lot longer than that to prove in Darwinian terms that our large brain, the organ we’re so proud of, really does give us the evolutionary edge.

Photo Alessandro Moggi

I should image that once they’ve considered our species’ chances of surviving for another 4,700,000 years, the number of people inclined to feel superior to an apricot tree is likely to drop drastically. Yet that’s the sense of evolution. Neither an apricot tree nor a cow can do a great deal to bring about their own extinction. Both species will become extinct eventually, like many others, but only as a result of such huge changes in the environment that they can no longer survive. Luckily, we’re talking about catastrophic events that do occur, but only every few million years. Mankind, on the other hand, never ceases to generate new ways of bringing about his own extinction; it almost feels as though he were working on an assembly line. But whatever else, if we do become extinct before the next 4,700,000 years have gone by, at least we’ll have proved that having such a highly developed brain wasn’t such an advantage after all. We’ll just have to wait and see.