by Riccardo Lami

Talking about family means discussing a personal, intimate topic in the life of every individual, a topic to which everyone feels bound in one way or another on the basis of their specific experiences, relationships and circumstances. The way the topic was addressed in the Family Matters exhibition held at Palazzo Strozzi in 2014, which explored how artists handle the topic, does not mean wondering what the family is in their eyes, so much as exploring the way in which it plays a crucial role in everyone’s life, indeed more so today than ever before.

The title of John Clang’s series of photographs, Being Together (2010–14), is an expression that almost sounds out of place in these times echoing with such words as self-isolation, quarantine and social distancing. But at the same time, it appears to meet a deep-seated need that is more topical than ever, the need not to be alone, the need to be part of a “family”: both our birth family and our chosen family.

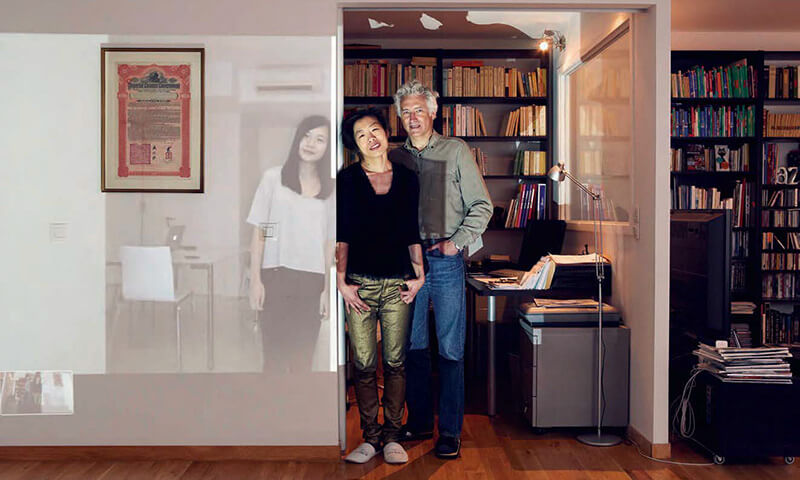

John Clang, Being Together (Family), 2010. Courtesy the artist and Pékin Fine Arts, Beijing

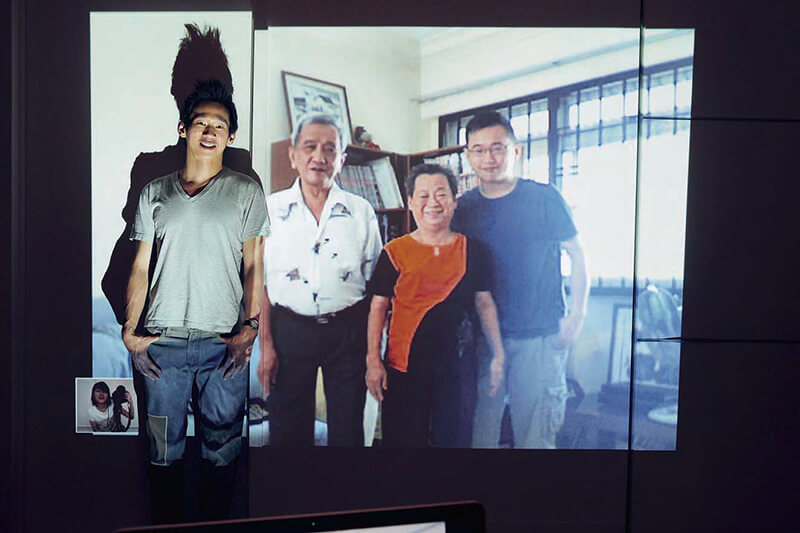

John Clang, Yeo family (New York, Sengkang), 2010, Courtesy the artista and Pékin Fine Arts, Beijing

Clang’s series comprises over forty portraits of families whose members are physically separated from one another, sometimes by even thousands of miles. In each photograph, through the use of a webcam projecting images on a 1:1 scale on the wall, several different people are connected with the place in which one or more members of their family are located. All the photographs are taken through live Internet connections as in any normal video call, and all the settings shown are the real homes of the people who live far away from their families. They are living rooms or sitting rooms, rooms filled with objects that reflect their daily lives. Each portrait creates a kind of “family reunion” in the non-place that is the photographic image, revealing a search for identity and belonging but, at the same time, also a deep sense of extraneousness and alienation.

John Clang, Goh family (Bellevue, Bedok), 2011, Courtesy the artist and Pékin Fine Arts, Beijing

John Clang, Lim family (London, Upper Serangoon), 2012, Courtesy the artist and Pékin Fine Arts, Beijing

A crucial aspect of the family portrait is the tension between the public and private dimensions, an element that underpins the work of Israeli artist Guy Ben-Ner. In his video entitled Soundtrack (2013) Ben-Ner, his children and a few friends create a sequence of images that are superimposed on part of the soundtrack from the Hollywood movie The War of the Worlds. The alien invasion in Spielberg’s film becomes the soundtrack for a series of unlikely domestic events. The work’s strength lies in its ability to create a short-circuit between reality and the imagination, in which the figure of the family becomes an ambiguous space, safe and dangerous at the same time, the epicentre of the zany irony that dominates the entire video.

Guy Ben-Ner, Soundtrack, 2013

Courtesy the artist and Pinksummer, Genova

Ever since the 1980s, in parallel with his output devoted to other issues, German photographer Thomas Struth has been working on a series entitled Familienleben (“Family Life”), a series of portraits generated by specific families, with the families of friends, colleagues and acquaintances captured in their respective homes. Typical of Struth’s work is the strong formal control that in this case underscores the focus on each individual detail such as the sitters’ gazes and expressions, their clothing or the setting. Each work becomes a kind of magnifying glass that highlights each family’s specific nature but also its broader exemplary value. Struth asks his sitters to look straight at the camera, concentrating as hard as they can and staying as still as possible. “No smiling boys or girls, no happy mums or dads. What I’m really interested in is giving my audience a place to look at that is a little uncertain and at the same time a little ambiguous.”

Thomas Struth, The Falletti Family, Florence, 2005

De Pont museum of contemporary art, Tilburg NL

Each picture portrays specific faces and situations but also becomes a model for the clearly defined construction of roles, hierarchies and dynamics. Alois Riegl had this to say about the portrait of a Dutch group in the 17th century: “[The family portrait] is neither an extension of the individual portrait nor yet the mechanical composition of individual portraits into a single whole. It is far more than that, it is the depiction of a corporation.” The individual portrayed is defined by his or her relationship with the other figures, i.e. as the father or mother of…, or the son or daughter of… and so forth. By the same token, people looking at a family portrait feel prompted to unravel the relationships on the basis of their own situation, linking the images to their own life, bonds and family. Unlike individual portraits or group portraits in which the sitters depicted are exalted in the features unique to them, the family portrait does not depict a distant or detached situation but a shared, family reality.

Thomas Struth, Untitled (New York Family 1), New York, 2001, De Pont museum of contemporary art, Tilburg NL

Thomas Struth, The Richter Family 2, Cologne, 2002, De Pont museum of contemporary art, Tilburg NL

The idea of the family portrait benefits from a counterpoised revisitation in Nan Goldin’s work. Famous for its heavily realistic, almost diary-like approach, her work has always revealed an inextricable link with her own life story. In her work, the family comes across as the result of an existential need: “all sticking together, based on the individual’s sense of incompleteness.” In her hands photography becomes a relational tool, and her entire career is a journey through images of encounter and connection: “I’ve never believed that a single portrait can determine a subject, but I do believe in a plurality of images testifying to the complexity of a life.” Her strong sense of spontaneity goes hand in hand with a stringent formal control that emerges quite clearly in her use of focus, in her construction of overturned perspective levels and in her careful composition of lights and lines.

Nan Goldin, Guido with his mother, grandmother and shadow, Turin, 1999, Guido Costa Projects & Matthews Marks Gallery

Nan Goldin, My parents kissing on their bed, Salem, MA, 2004, Courtesy the artist

In some images Nan Goldin conjures up a generational confrontation within a single family group, while in others she portrays such taboos as parents’ sexuality. As she says herself: “I don’t believe that a single portrait can express what a person is.” Her work does not set out to provide a sitter with a certificate of his or her identity so much as to capture a gaze that reveals a human relationship, transforming it into a memory capable of withstanding the passage of time.

Cover photo: John Clang, Tye family (Paris, Tanglin), 2012, Courtesy the artist and Pékin Fine Arts, Beijing