by Ludovica Sebregondi

It feels bizarre today to consider Palazzo Strozzi – home to the Fondazione Palazzo Strozzi which uses the premises to plan and organise art exhibitions, to the Gabinetto Vieusseux, to the Istituto Nazionale di Studi sul Rinascimento and to the Scuola Normale Superiore, along with the Caffè and Bottega Strozzi – as a private home, the symbol of a family, embodying that family’s determination to “make a comeback”. Yet that is exactly what it was for Filippo Strozzi (1428–91), who devoted an enormous amount of energy to devising it and to having it built. Filippo’s father Matteo had been exiled from Florence because the family had taken up a stance against Cosimo de’ Medici, and Filippo himself was exiled to Naples, where he forged a bond of friendship with Ferdinand of Aragon and his son Alfonso. They interceded on his behalf with Cosimo de’ Medici’s son Piero and won him a reprieve, so Filippo was able to return to Florence after twenty-five years. He wrote to his mother on 27 November 1466, annoucing in a joyous tone veined with humour that: “Sunday evening, God willing, you will have me there. Make sure there is something other for dinner than the sausage I hear you are planning to serve.”

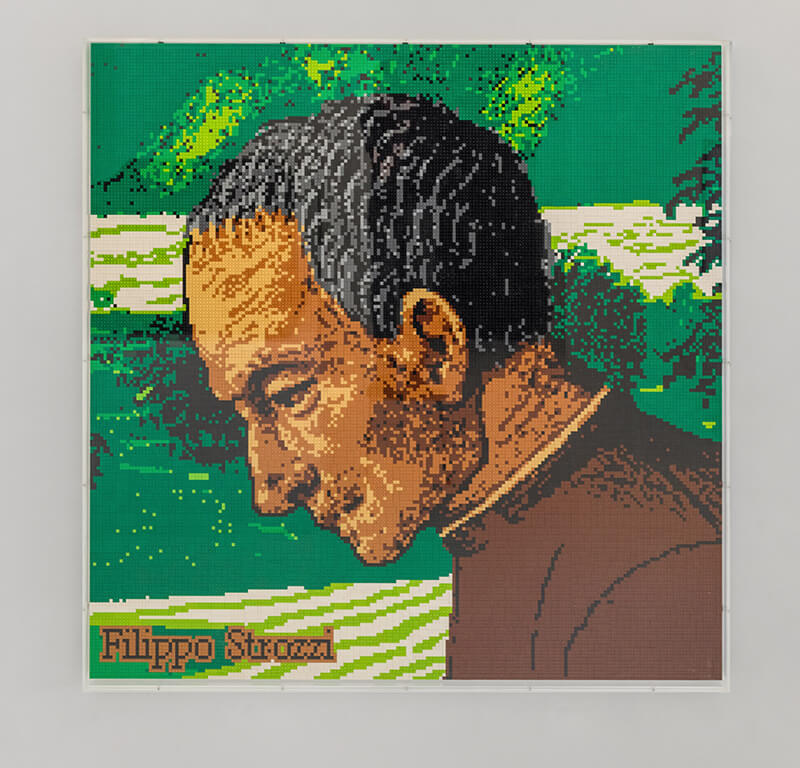

Ai Weiwei, Filippo Strozzi in LEGO, 2017, Florence, Museino di Palazzo Strozzi

Courtesy of Ai Weiwei Studio

Once he was back in his native city, Filippo said: «I cannot cease thinking and drawing, and if God grants me a long and healthy life I hope to achieve something memorable». His plan was to erect the grandest building in Florence both to display and to testify to the power of his family and its rebirth. The operation was to prove complex and it took Filippo from 1473 to 1489 to acquire the land on which to build his future palazzo in a key area of the city, at the crossroads of what are now Via Tornabuoni and Via Strozzi. He had to demolish the many buildings he bought and to eat into the square in front of the area, thus altering the very fabric of the city. To make sure that his project was a success, he turned to the astrologer Benedetto Biliotti to establish the exact moment for laying the foundation stone. Biliotti advised him that the most propitious moment would be at dawn on 6 August 1489, over 530 years ago. That morning, Filippo wrote in his memoirs: “As the sun rose from behind the hill, in the name of God and of a good beginning for me and all my descendants, I began to found the aforementioned house of mine and I laid the first stone of its foundations”. At the chosen moment “the sign of Leo was rising over the horizon in the eastern sky, which […] means that the building will last for ever and be the home of great and noble men of worthy estate”

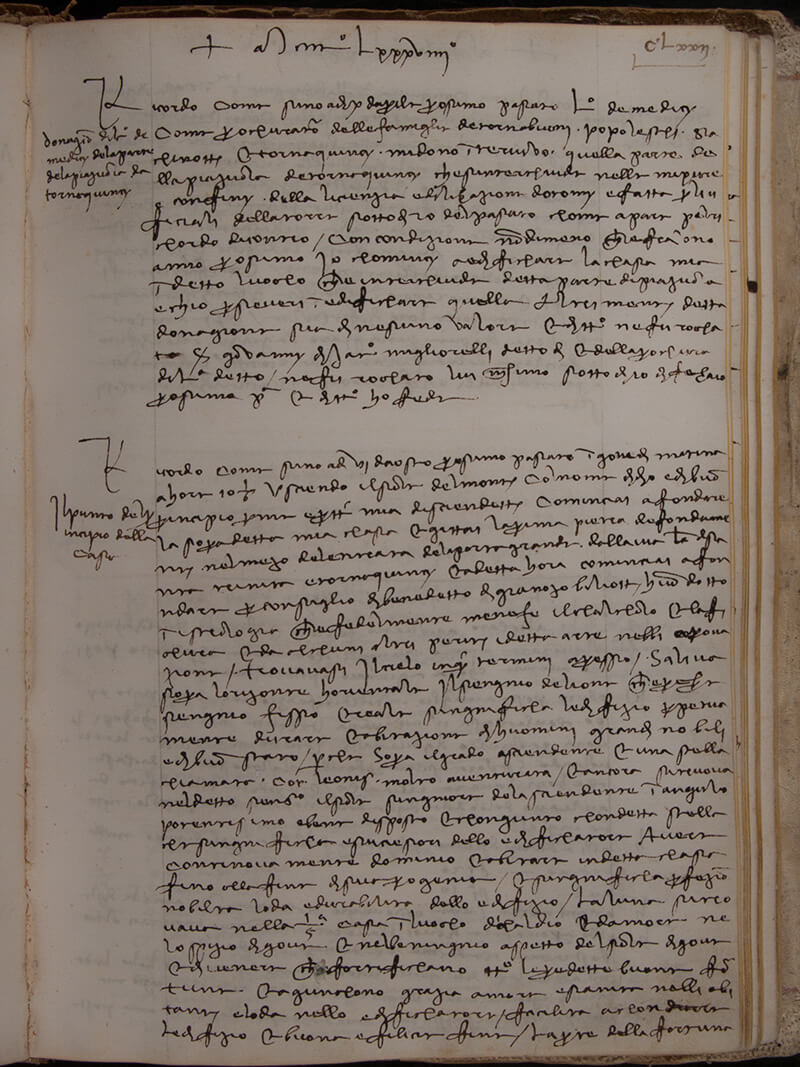

Filippo Strozzi’s register of debtors and creditors, 1484–91, Florence, Archivio di Stato, Carte Strozziane, Quinta serie, 41, fol. 172

We find evidence of the extent to which the Florentines considered the event exceptional in the memoirs of a spicer named Tribaldo de’ Rossi whose shop stood a little way off, across the street from the church of Santa Trinita. He tells us: “On 6 August 1489, at sunrise, the masons began to found said palazzo for Filippo Istrozi.” As Tribaldo was looking down into the trench nine metres deep, Filippo in person came up to him and said: “Take a stone and throw it in, and so I did, and then I put my hands in my pouch in his presence and took out an old coin, a quatrino gigliato, to throw it in, which he did not want me to do, but in memory of the event I threw it in all the same and he was content.” Tribaldo also sent “Tita our servant” to fetch his two sons at home, telling her to dress them up in their Sunday best and bring them to see “said foundations.” He took his eldest, “Ghuarnieri, in my arms and squat down with him and gave him a quatrino gigliato and he threw it in and a bunch of small damask roses that he was holding, I got him to throw them in too, I told him thou shalt remember this.”

The ritual of having the children wear their best clothes to solemnise the event and of having them throw coins and flowers as a spontaneous, unpremeditated act to bring good luck is combined here with the traditional gesture, when laying the foundation stone of a place of worship, of urging those in attendance to throw a stone into the trench – all of them ritual, almost magical gestures thought to bring good luck and to ward off evil.

Benedetto da Maiano or Giuliano da Sangallo, Model of Palazzo Strozzi, c. 1489

Museino di Palazzo Strozzi, on loan from the Museo Nazionale del Bargello

Despite the fact that we still have the Libri della Muraglia, or building records, containing daily progress reports and building costs, we do not actually know the name of the architect who designed the palazzo. Giuliano da Sangallo and Benedetto da Maiano each produced a model, but only one model has come down to us and we are not certain which of the two architects made it. Now in the Museino, it is very similar to the palazzo ultimately built, except that the latter is over three and half metres taller. Simone del Pollaiolo, known as “Il Cronaca,” was appointed foreman of the works shortly after work began in 1490, and the palazzo had risen as high as the first floor by the time Filippo died in 1491.

Corbel in Palazzo Strozzi with the family coat-of-arms and Filippo’s personal “devices”

Filippo wanted the corbels to bear the family coat-of-arms with its three crescent moons, along with his own personal “devices” comprising allegorical phrases accompanied by a figure formulating thoughts or maxims. One device shows a falcon with its wings outspread, tearing its feathers on the trunk of an oak tree and accompanied by the motto “Sic [et] virtus expecto” (I wait, and so does virtue); another shows a lamb with the words “Mitis esto” (Be gentle) – thus an encouragement to display the patience and resilience which allowed Filippo to survive in times of adversity during his long exile and to then succeed in building and in handing down the splendid palazzo that he was so determined to erect, the boast not only of his family but of the entire city and today a world-renowned symbol of the Renaissance.